Welcome back, dear nerds. Today we’re decoding the magic behind those eerily human-like responses from ChatGPT, Claude, and their AI kin. No, it’s not witchcraft—it’s statistics, linear algebra, and an unhealthy obsession with training data.

Let’s get you from “LL-what?” to “Aha!” in one post.

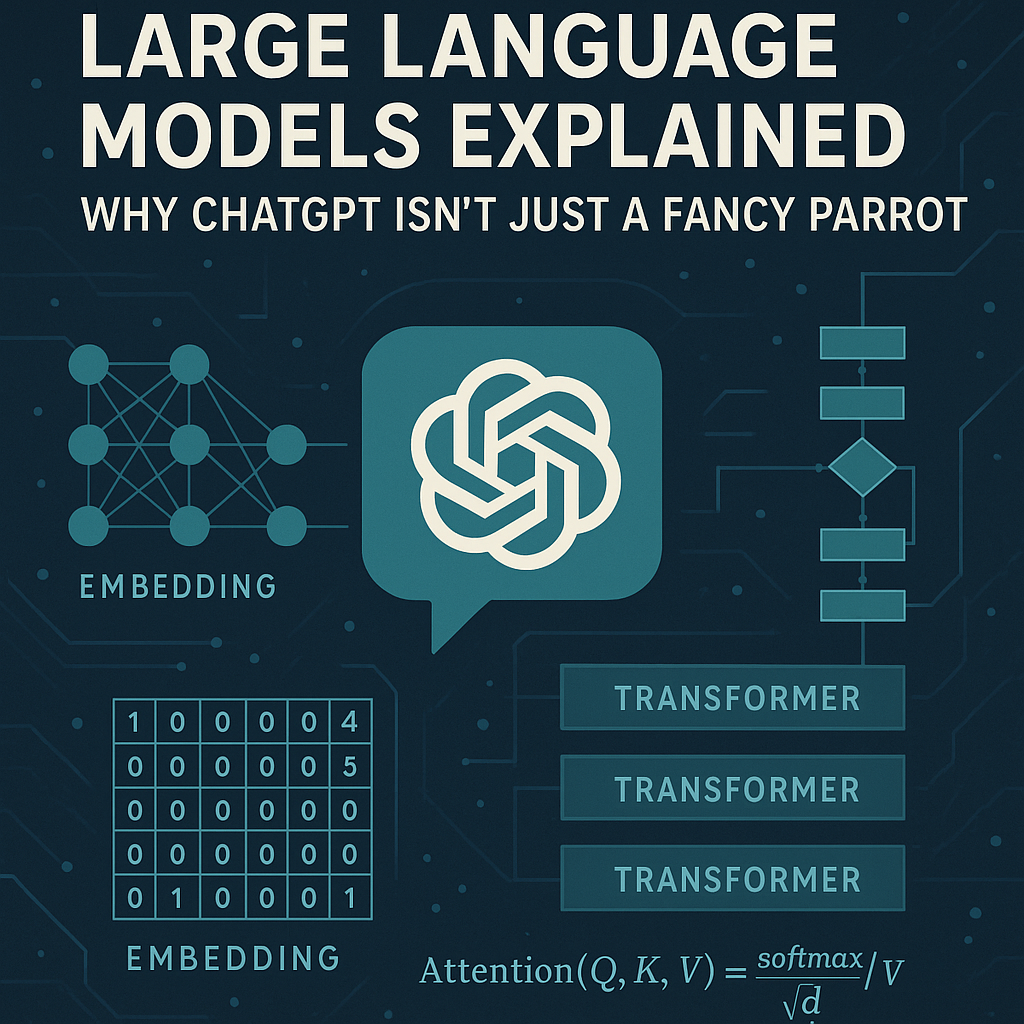

What Is a Large Language Model?

A Large Language Model (LLM) is a type of artificial intelligence that generates human-like text based on patterns it’s learned from a mind-numbing amount of data. Think: Reddit rants, Wikipedia pages, codebases, blog posts (maybe even this one)—all chewed up, digested, and encoded into a massive neural network.

At its core, it predicts the next word in a sentence. That’s it. No deep thoughts. Just brutal pattern matching.

But it’s really good at it.

The Core Math Behind It: Linear Algebra & Probabilities

Let’s nerd out.

1. Tokenization: The Data Diet

Before any math happens, text is converted into tokens (which are kind of like words, but also not—e.g., “unbelievable” might become [“un”, “believ”, “able”]). These tokens are then mapped to numbers using an embedding matrix.

2. Embeddings: The Math Soup Begins

Each token gets a dense vector—think: a list of hundreds or thousands of numbers representing its meaning in a high-dimensional space. Close vectors = similar meanings.

Mathematically, if we have a vocabulary of size $V$ and embedding dimension $d$, our embedding matrix $E \in \mathbb{R}^{V \times d}$ maps each token to its vector representation.

3. Transformers: The LLM Engine

The transformer architecture (introduced by Vaswani et al. in 2017) is the secret sauce. Its key innovations:

Self-Attention Mechanisms

The famous “self-attention” lets the model weigh the importance of different words relative to each other. In a sentence like “The animal didn’t cross the road because it was too tired”, it helps figure out what “it” refers to. (Spoiler: not the road.)

The core formula for scaled dot-product attention is:

$$\text{Attention}(Q, K, V) = \text{softmax}\left(\frac{QK^T}{\sqrt{d_k}}\right)V$$Where:

- $Q$ (Query) represents what information we’re looking for

- $K$ (Key) represents what information is available

- $V$ (Value) represents the actual content

- $d_k$ is the dimension of the key vectors

The scaling factor $\frac{1}{\sqrt{d_k}}$ prevents the dot products from growing too large, which would cause the softmax to output extreme values (near 0 or 1), leading to vanishing gradients.

Multi-head Attention

Not one, but multiple attention mechanisms running in parallel—because more is more. Each head learns different relationships:

$$\text{MultiHead}(Q, K, V) = \text{Concat}(\text{head}_1, ..., \text{head}_h)W^O$$Where each head is computed as:

$$\text{head}_i = \text{Attention}(QW_i^Q, KW_i^K, VW_i^V)$$With learned projection matrices $W_i^Q \in \mathbb{R}^{d_{model} \times d_k}$, $W_i^K \in \mathbb{R}^{d_{model} \times d_k}$, $W_i^V \in \mathbb{R}^{d_{model} \times d_v}$, and $W^O \in \mathbb{R}^{hd_v \times d_{model}}$.

Feedforward Networks

After attention, it’s time to pass the info through a few fully connected neural layers. This is where the model learns abstract features:

$$\text{FFN}(x) = \max(0, xW_1 + b_1)W_2 + b_2$$This is typically a two-layer network with ReLU activation, expanding to a higher dimension (often 4x) and then projecting back.

Positional Encoding

Since transformers don’t inherently understand word order, we sprinkle some sine and cosine math magic to give the model a sense of sequence:

$$PE_{(pos, 2i)} = \sin\left(\frac{pos}{10000^{2i/d_{model}}}\right)$$$$PE_{(pos, 2i+1)} = \cos\left(\frac{pos}{10000^{2i/d_{model}}}\right)$$Where:

- $pos$ is the position in the sequence

- $i$ is the dimension index

- $d_{model}$ is the model dimension (512 in the original paper)

This creates unique patterns for each position that the model can learn to interpret. The beauty? For any fixed offset $k$, $PE_{pos+k}$ can be represented as a linear function of $PE_{pos}$, making it easy for the model to learn relative positions.

4. Training with Gradient Descent

The model is trained to minimize the difference between its predicted token and the actual token in the training data. This is done with a cross-entropy loss function:

$$L = -\sum_{i=1}^{V} y_i \log(\hat{y}_i)$$Where $y_i$ is the true probability (1 for the correct token, 0 otherwise) and $\hat{y}_i$ is the predicted probability.

Optimization happens via gradient descent with the Adam optimizer:

$$\theta_{t+1} = \theta_t - \alpha \cdot \frac{m_t}{\sqrt{v_t} + \epsilon}$$Where $m_t$ and $v_t$ are the first and second moment estimates of the gradients.

Over weeks or months of training on mega-clusters of GPUs (cue the electricity bill), the weights in the neural network are adjusted until the model can generate coherent text.

Why It Works (and Sometimes Doesn’t)

LLMs don’t understand language like humans. They excel because:

- They’ve seen everything (almost): Trained on vast, diverse datasets (often over 1 trillion tokens).

- They model context like a boss: Thanks to attention, they can capture long-range dependencies across thousands of tokens.

- They optimize for likelihood: Which means their goal is to sound correct—not necessarily be correct.

This leads to impressive fluency… and occasional confident nonsense. (We call it “hallucination,” because “lying” sounds rude.)

The transformer’s computational complexity is $O(n^2 \cdot d)$ where $n$ is sequence length and $d$ is the model dimension—that’s why context windows have limits! However, modern models have pushed these boundaries significantly, with some accepting over 100,000 tokens.

Claude, ChatGPT, and Friends: The Architecture Wars

All these models share the same DNA—transformers. But the implementation details matter enormously:

Model Architecture Evolution

- GPT-4: While OpenAI hasn’t officially disclosed the architecture, industry reports suggest it uses a Mixture of Experts (MoE) approach with approximately 1.76-1.8 trillion parameters total, consisting of multiple expert models (possibly 8-16 experts) that are selectively activated

- Claude: Uses Constitutional AI for safety modeling, developed by Anthropic with a focus on harmlessness and helpfulness

- Gemini 1.5 Pro: Google’s entry featuring massive context windows (up to 2 million tokens!) and native multimodal capabilities

Training Costs: The Billion Dollar Race

The financial scale has exploded:

- GPT-3 (2020): ~$4.6 million in compute costs

- GPT-4 (2023): Sam Altman confirmed over $100 million in training costs

- Gemini Ultra (2024): Estimated at $191 million

- Future models: Potentially approaching $1 billion+ as companies race to scale

These costs include:

- Compute: 25,000+ NVIDIA A100 GPUs running for 90-100 days for GPT-4-class models

- Data preparation and cleaning

- Human feedback for RLHF (Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback)

- Multiple training runs and experiments

Alignment Methods

Modern LLMs use sophisticated techniques to make outputs helpful and safe:

$$J(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{(x,y) \sim D_{RL}}[r_\phi(x, y)] - \beta \mathbb{D}_{KL}[\pi_\theta(y|x) || \pi_{ref}(y|x)]$$Where $r_\phi$ is a learned reward model and the KL term prevents the model from deviating too far from a reference policy.

The Mixture of Experts Revolution

One of the most significant architectural innovations is the Mixture of Experts (MoE) approach:

How MoE Works

Instead of activating all parameters for every token, MoE models:

- Divide the model into multiple “expert” sub-networks

- Use a routing mechanism to select which experts process which tokens

- Typically activate only 2-4 experts per token, dramatically reducing computation

Benefits

- Efficiency: Can scale to trillions of parameters while maintaining reasonable inference costs

- Specialization: Different experts can specialize in different domains or tasks

- Performance: Achieves better results than dense models of equivalent computational cost

Examples in the Wild

- Mixtral 8x7B: Open-source MoE with 8 experts of 7B parameters each

- GPT-4: Reportedly uses 8-16 experts (unconfirmed by OpenAI)

- Switch Transformers: Google’s research pushing MoE to extreme scales

The Scale Game

Modern LLMs are pushing the boundaries of what’s computationally possible:

By the Numbers

- Parameters: 100B to 1.8T+ (GPT-4 reportedly has ~1.76-1.8 trillion)

- Training data: 10-13 trillion tokens (GPT-4 scale)

- Training FLOPs: ~10²⁴-10²⁵ (more calculations than grains of sand on Earth)

- Context windows: From 8K tokens (early 2023) to 2M tokens (Gemini 1.5 Pro)

Scaling Laws

Performance follows predictable patterns:

$$L(N) = \left(\frac{N_c}{N}\right)^{\alpha_N}$$Where $L$ is loss, $N$ is model size, $N_c$ and $\alpha_N$ are constants. This relationship has held remarkably well, though we’re beginning to see diminishing returns requiring new innovations.

What’s Next? The Future of LLMs

The field is evolving rapidly:

- Efficiency Improvements: Techniques like quantization, distillation, and specialized hardware

- Multimodal Integration: Native understanding of text, images, audio, and video

- Longer Context: Moving towards unlimited context through architectural innovations

- Better Reasoning: Chain-of-thought, tree-of-thought, and other structured reasoning approaches

- Domain Specialization: Models fine-tuned for specific fields (medicine, law, science)

References & Further Reading

- Vaswani, A., et al. (2017). “Attention Is All You Need”

- OpenAI. “GPT-4 Technical Report”

- Anthropic. “Constitutional AI”

- Jay Alammar. “The Illustrated Transformer”

- Kaplan, J., et al. (2020). “Scaling Laws for Neural Language Models”

- Shazeer, N., et al. (2017). “Outrageously Large Neural Networks: The Sparsely-Gated Mixture-of-Experts Layer”

- Fedus, W., et al. (2022). “Switch Transformers: Scaling to Trillion Parameter Models”

Final Thoughts

Next time someone says ChatGPT is just regurgitating text, remind them that it’s not just that—it’s high-dimensional vector arithmetic trained across billions of examples and thousands of GPUs to predict what comes next, better than most humans.

The math is elegant. The scale is mind-boggling. The costs are astronomical. The results? Sometimes brilliant, sometimes bonkers, always fascinating.

(And then use it to write your grocery list. Just because you can.)

Remember: With great compute power comes great responsibility. Use your LLMs wisely, and always fact-check when it matters.